Heavy-handed tactics by Tanzania’s government to silence opponents, the media and civil society threaten to undermine the legitimacy of the presidential election Wednesday — and the country’s reputation for political stability.

Western diplomats, opposition leaders and human rights groups accuse President John Magufuli of trying to fend off his main challenger, Tundu Lissu, by cracking down on political activity, restricting and barring journalists, and passing laws that tighten his grip on the country.

“These conditions really made the situation very difficult,” said Oryem Nyeko, a specialist on Tanzania for Human Rights Watch, who warned that the elections may not be “as free and fair as they should be.”

Lissu, speaking to The Washington Post from the airport in Arusha, accused the government of rigging the vote by stacking the electoral authorities with ruling-party members. He warned of mass protests if the result is perceived as unfair and security forces continue a violent crackdown on the opposition.

In that case, “we will not concede the elections, and we have said this time around, it will be decided by the masses on the streets,” said Lissu, who complained that the government was refusing to allow his helicopter to fly him to Dar es Salaam for his closing rally.

Such a threat of instability is unheard of in one of Africa’s most peaceful democracies, where the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi has been in power in some form since independence in 1961 under founding father Julius Nyerere. Today Tanzania is lauded by investors for the economic growth of more than 6 per cent a year, which has lifted it to middle-income status.

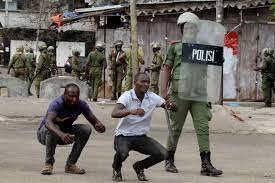

A police officer enforces pre-election laws in Zanzibar, Tanzania, on Oct. 27. (Anthony Siame/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock)

But violence already has erupted, and an atmosphere of fear pervades Tanzania. In the latest outburst, at least three people were killed, including a mother of six, and dozens injured Monday when security forces fired tear gas and bullets at crowds in the semiautonomous region of Zanzibar, according to human rights activist Thabit Juma. Some news reports later said as many as nine people were killed in the shooting.

As voters went to the polls Wednesday, independent observers said the government had imposed restrictions on some social media sites, issued a directive to block text messaging and slowed the Internet.

Tanzania Elections Watch, a regional group made up of prominent personalities, said in a statement it was “alarmed by the clampdown on communication channels” and called on the government to respect constitutional protections of freedom of expression.

Twitter also confirmed that it was seeing some blocking and throttling on its platform, cautioning that “Internet shutdowns are hugely harmful, and violate basic human rights and the principles” of an open Internet.

The government has rejected criticism of intimidation and human rights abuses. A government spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.

On the campaign trail, Magufuli has touted mega-infrastructure investment projects by his government to build roads, ports and power plants as the reason voters should give him a second five-year term. Supporters call him “Bulldozer” for pushing through policies.

The main opposition parties have united behind Lissu, the candidate for the Chadema party, who is popular with young voters frustrated by a lack of opportunity and energized by his message of “freedom, justice and people-centred development.”

Lissu returned from exile in Belgium this year after an attempted assassination in 2017 in which he was shot 16 times. In June another Chadema opposition leader, Freeman Mbowe, was attacked by unknown assailants after he accused the government of covering up Tanzania’s coronavirus outbreak. Magufuli fired senior government health officials and halted public reporting of coronavirus cases in April, declaring that the virus had been defeated through prayer.

An Oct. 12 report by international rights group Amnesty International accused Magufuli of becoming an autocratic ruler since his election in 2015 and using the “law to systemically and deliberately clamp down on people’s inalienable human rights.”

The government’s actions were worrying and an unhealthy sign for a country positioning itself for greater growth and development, Deprose Muchena, Amnesty International’s director for eastern and southern Africa, said at the report’s launch.

Large foreign donors have become increasingly alarmed by the government’s rising attacks on human rights in recent years.

In November 2018, the World Bank froze $1.7 billion in loans to Tanzania over a policy that banned pregnant students from public schools and a law making it illegal to question official statistics, while Denmark, the country’s second-biggest donor, withheld $10 million in aid over reported homophobic comments by an official. The World Bank resumed lending in September 2019.

On Friday, U.S. Ambassador to Tanzania Donald J. Wright expressed concern about reports of government security agents disrupting opposition campaigning, but he said there was still time to restore credibility to the election by allowing independent monitors and ensuring more transparency of the vote.

Lissu’s conditions for accepting the election results include opposition monitoring of the vote, with results recorded and given to opposition polling agents, and election return officers declaring the result, along with the cessation of violence against opposition election activity by security forces.

Supporters of Zanzibar’s main opposition party attend a campaign rally in Nungwi on Oct. 24. (Marco Longari/AFP/Getty Images)

According to Tanzania’s election authority, more than 29 million people have registered to vote. Magufuli won the 2015 election with 58 per cent of the vote, while opposition alliance candidate Edward Lowassa took 40 per cent. Lissu claims opposition polling shows the majority of voters support him this time.

“I’m guessing that President Magufuli is worried by the political gains of the opposition, and that’s why he has taken the steps that he has to close down the political space,” said Bronwyn Bruton, director of programs and studies at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center in Washington. “This is not something that a confident leader does.”

She said it was too early to say whether the election was free and fair but warned the damage may already have been done.

“My number one concern so far is the lack of a level playing field, which makes it seem like there might be some manipulation of the actual election results or an effort to suppress the votes of opposition supporters,” Bruton said.

With governments throughout the world dealing with the economic and social fallout from the coronavirus pandemic, she said the international community may be willing to act only if violence erupts.

“People just don’t have the image of Tanzania as a backsliding, failing democracy,” Bruton said.